What are we to make of

that fat little boy with the strange haircut, and those old

men standing over him with their ridiculous khaki pudding-bowl headgear? It

seems incredible that between them the great powers cannot rein in, neutralize,

or simply manage the cranky huff and puff of a wholly non-viable

totalitarian micro-state, whose continuing existence is in nobody’s interest—least

of all its own benighted, brainwashed citizens—but whose irrational behavior now constitutes

a terrible threat to the stability of the rest of the world. True, the problem

of North Korea seems almost by definition doomed to evade the best attempts of

professional diplomats and policy makers everywhere even to grasp, far less to solve it. One does

wonder what goes through the mind of each over-decorated North Korean general

upon retiring to bed, or upon getting up in the morning. What do they

think they are doing, other than holding on—and hoping that baby Kim

continues to read from his script? This morning’s New York Times seems to

follow the prompts of the Obama administration in regarding the present threats

to dispatch probably fictitious nuclear missiles to targets on the continental

United States (including the east coast) as no more than the mad bellicosity of

a regime determined to reinforce for domestic consumption the artificial

reputation for military daring of its limitlessly horrid Baby Doc. However, even if you

allow for the old-fashioned propaganda factor, threats are threats, and it is certainly unsettling

to know that those nuts in North Korea have concocted a map with straight-line

trajectories leading to a spot, for example, no more than an hour’s drive from

where I sit. My own feeling is that it would be far, far better if there were

no such threats, and certainly no more Kims. Is this too much to seek from such realistic

minds as hold sway in Beijing, Washington, and the Kremlin? I mean, enough for Heaven’s sake!

Saturday, March 30, 2013

Tuesday, March 26, 2013

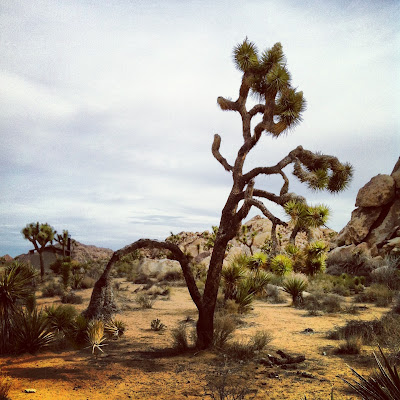

Joshua Tree

The Joshua

Tree National Park is an easy forty-five minute drive from Palm Springs, California,

due north across the Coachella Valley, past Hot Desert Springs, up through the

Morongo and Yucca Valleys, and into the high Mojave Desert, on the northern

side of the Little San Bernardino Mountains.

Entering the park just outside the town of Joshua Tree, and well before you reach the U.S. Marine Corps base town of Twenty-Nine Palms, at first you navigate an environment that is dominated by huge monzogranite outcrops rising from the surrounding desert floor, liberally dotted with Yucca brevifolia, the eponymous tree. This enchanting plant was originally named by Mormon travelers, who recognized in its shape a gesture worthy of the conquerer of Jericho and of Canaan. Like certain grasses and orchids, the Joshua tree is a very large member of the Agave family.

These wonderful emanations of the high desert twist and writhe and, just now, flower—not so much in stands or sopses but nevertheless in glorious profusion, each producing a performance of strange and ritualistic individualism.

A day spent wandering through Joshua Tree, preferably more, is enough to impress upon even the most occluded soul the hopeless inadequacy of the English word desert, for instead one senses, as in many parts of Outback Australia, that places such as this are the fons et origo, the birthing places of life itself. How I long to go back!

Entering the park just outside the town of Joshua Tree, and well before you reach the U.S. Marine Corps base town of Twenty-Nine Palms, at first you navigate an environment that is dominated by huge monzogranite outcrops rising from the surrounding desert floor, liberally dotted with Yucca brevifolia, the eponymous tree. This enchanting plant was originally named by Mormon travelers, who recognized in its shape a gesture worthy of the conquerer of Jericho and of Canaan. Like certain grasses and orchids, the Joshua tree is a very large member of the Agave family.

These wonderful emanations of the high desert twist and writhe and, just now, flower—not so much in stands or sopses but nevertheless in glorious profusion, each producing a performance of strange and ritualistic individualism.

Last

Wednesday I was quite alone, and the effect was one of perfect eeriness. It did not matter that the morning was overcast, for this lent considerable softness and subtlety to the textures of the land, and a definite blueness to certain of the grasses. The

cheerful ranger at the front gate told me that mountain sheep had been spotted

on an escarpment earlier that morning, but I could see nothing as large through my binoculars, only the scratchy junipers, other high-desert conifers, and

these marvelous jumbo Yuccas.

At

length you descend almost imperceptibly towards the great Pinto Basin, which

forms a region of transition between the high Mojave and the hotter and bleaker

but no less fecund Sonoran Desert. These slight shifts in altitude produce an

immediate and colossal transformation in the flora.

The

Joshua trees come to a sudden halt, and make way for smaller succulents and drier, more delicate

grasses and cacti to match the higher temperatures, the pert Cylindropuntia bigelovii or Cholla

cactus, for example, so winning and so absurd, as well as many others, some spiky, some fluffy, others just

now erupting into their rare and almost miraculous moments of flower. The man holding the stop sign where the road works commenced drew my attention to this one, which I would never have seen without careful directions from the road.A day spent wandering through Joshua Tree, preferably more, is enough to impress upon even the most occluded soul the hopeless inadequacy of the English word desert, for instead one senses, as in many parts of Outback Australia, that places such as this are the fons et origo, the birthing places of life itself. How I long to go back!

Sunday, March 24, 2013

Palm Springs

I have just returned from

a few days’ rest in Palm Springs, California. I have grown very attached to

that lovely place since I started going there ten years ago. Situated

approximately 120 miles due east of Los Angeles, Palm Springs occupies a portion

of desert at the western end of the wide, flat Coachella Valley, hard by the magnificent

San Jacinto Mountains. The highest peak is roughly a mile and a half straight

up from the valley floor, almost 11,000 feet above sea level, and Palm Springs cleaves to its rocky skirts like a

playful, mostly indulged infant. The valley itself is bounded by the Little San

Bernardino Mountains to the north, and the San Jacinto and Santa Rosa ranges in

the south, and subsides almost imperceptibly into the Salton Sea, an enormous lake at the

eastern end, not all that far from the Mexican border. The San Andreas fault runs right the way through the middle of the

Coachella Valley, and is clearly visible from any point of elevation—a slightly

sinister reminder that the entire region dwells at the junction of the great North

American and Pacific plates which everybody knows are pushing very

hard in opposite directions, harder here than elsewhere in California because of a kink in the fault line that is said to concentrate greater than usual pressure. This raises the obvious question, I suppose, as to why one would ever choose to settle in the locality, but the same might well have been regularly asked of Naples or Osaka for the past 3,000 years. The long-vanished Pinto culture and, latterly, the Serrano and Cahuilla peoples have all lived in comparative harmony with this environment for approximately 4,000 years. Palm Springs and the wider Coachella Valley also

lie close to the intersection of the Sonoran and Mojave Deserts, and their

point of transition forms one of the most remarkable, unspoiled natural

environments in the entire southwest: the high desert of the Joshua Tree National Park, and about

that I shall write separately.

Hence the existence here of the extraordinarily

surreal-looking San Gorgonio Wind Farm, whose 3,218 slowly rotating

windmills deliver on average 615 megawatts, roughly the same amount of

electricity as a smallish nuclear power plant in fully working order.

Strutting in snowy-white

ranks across the desert floor; taking up statelier positions on the

adjacent foothills, and seen between the rocky escarpments and the cloudless blue

sky they form a haughty, silent, and vaguely weird presence, at times

mesmerizing in scale and rhythm. Skirting these, indeed concentrating on ignoring them, you follow the Sonny Bono Memorial Highway (Route

111), which after twenty minutes or so turns into North Palm Canyon Drive, and suddenly you find yourself

entering an apparently endless grid of wide avenues mostly planted with tall,

slender palms. These form

the great green bowl of Palm Springs. The howling wind of San Gorgonio gives

way to desert warmth, a zephyrous micro-climate, to which the last few

generations of Hollywood retirees (but not only) have resorted for leisure, exercise, resuscitation, shelter, or peace,

often all these things at once. And in doing so, they have created a sort of

oasis of modernist design in mostly subtle harmony with the dry, hot, dreamy

climate. I often ask myself what in the American character contrived to discover the languorous pleasure, the joy even, of holiday-making in the desert, while we Australians cannot, it seems, be coaxed away from our ocean beaches? Perhaps this discovery yet awaits us, or is jealously guarded by a canny few the better to keep the masses at bay. Who knows?

These days I

prefer to fly directly to Palm Springs, and rent a car at the airport. The

airport itself is, I think, among the most beautiful in the world, a facility

whose innards were wisely replaced with an open-air desert garden replete with citrus trees and palms and flaming bougainvillea and chairs and tables. In the

almost inconceivable event of rain, one may borrow an umbrella after you go through

security (back there in the distance), and return it once you reach your departure gate (up an escalator and over one’s shoulder in this view).

The main disadvantage of these arrangements is the sense of sadness and loss

you experience upon having to depart, and leave behind that astonishing

mountain. I could stare at the changing light on its flank from dawn until the

sun descends over the other side in the late afternoon, indeed I have been

doing so for much of the past week, and am now already plotting and planning my return.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)